Dr. Henry Friedman inspires cancer patients with his optimism

--Originally published by The Duke Chronicle on Dec. 15, 2016

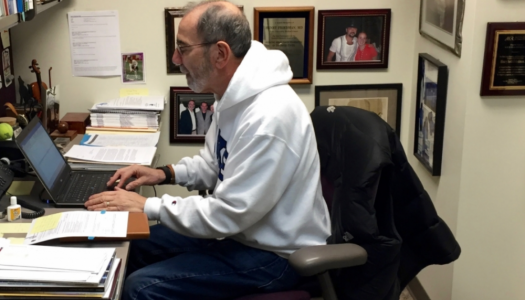

In a small physician’s office at Duke’s cancer clinic, Dr. Henry Friedman is looking through emails on his iPad. The lean 64-year-old with a scruffy gray beard and round spectacles is in his traditional daily garb—a white Duke hoodie, blue jeans and grey Brooks running shoes. Around him, other doctors and nurses gaze at MRI scans.

Suddenly, word arrives that his next patient is ready. Friedman puts down the iPad and accompanies his nurse clinician, Rosemary Ketring, into an exam room where they hug an older woman.

Friedman helped coin the brain tumor center’s motto—“At Duke there is hope.”

For this check-up, Friedman has good and bad news. The woman’s brain tumor has grown. But now she can receive Duke’s new, groundbreaking polio immunotherapy. She looks worried and stares at him with glossy eyes, but doesn’t respond.

“Be optimistic, but a little nervous,” Friedman tells her. “A little nervous is good.”

Despite his more than 30 years of experience treating the most lethal forms of cancer, Friedman—a lead neuro-oncologist and deputy director at the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center—is as hopeful as ever. He’s seen treatments improve and has also relied on his family, different responsibilities and positive demeanor to stay sane as most of his patients die.

Clinical consultations and patient checkups on Mondays and Tuesdays are just part of what he does. He helps oversee one of the country’s premier brain tumor centers, works with drug companies to create new reagents and has led efforts to develop new cures.

He used to treat more children and adults. But as the brain tumor center has seen an influx of people with brain cancer during the last five years, he’s now more involved with counseling new patients and referring them to different physicians at the center.

* * *

At Empower Personalized Fitness, Friedman is alone on a stationary bike, glancing through emails on his iPhone. He is halfway through his 30-minute, six-mile ride and will lift dumbbells, run in place and stretch with a personal trainer afterwards.

A torn rotator cuff has been nagging him. He grimaces when he reaches behind him or raises a weight too high in the air. But he’s unsure about whether he wants to see a sports medicine specialist—he has no time for shoulder surgery.

Friedman goes to the gym four days a week after leaving the hospital. He started exercising routinely 15 years ago to reduce his high cholesterol and gut, which has since disappeared. But as it does for so many other people, the gym also helps calm his frustrations.

According to the Society for Neuro-Oncology, more than 40 percent of neuro-oncologists suffer from burnout. In a field where three out of every five patients die less than a year after diagnosis, doctors regularly experience depression and emotional exhaustion and often become cynical about their work.

Friedman doesn’t remember how many of his patients have died and doesn’t want to. Treating people who have families or are the same age as his son and daughter has always been hard. But he depends on what he calls “protective mechanisms” to bolster his emotions and help him cope.

In addition to exercise, his family is a main mechanism for dealing with the stress. Friedman’s wife, Dr. Joanne Kurtzberg, is the director of Duke’s cell therapy and bone marrow transplant programs. Kurtzberg along with his 33-year-old son and 29-year-old daughter are a source of emotional strength for Friedman, and help him live a regular life outside the hospital.

At home, Friedman and Kurtzberg try to avoid talking about work. He enjoys going on walks and playing racquetball when his shoulder doesn’t hurt. And when they’re both not traveling, they watch TV shows most nights. He prefers zombie, werewolf and vampire shows like “Bitten” or “Van Helsing,” but they usually agree on “The Big Bang Theory” or “Madam Secretary.”

“He tends to separate from work,” Kurtzberg says. “He watches a lot of what I consider bad TV shows. He does normal life stuff.”

Other responsibilities outside of the brain tumor center also help him stay fresh. He helped create Duke’s Collegiate Athlete Pre-medical Experience, a mentoring program for female varsity student-athletes. And as a staunch feminist, he sits on the national advisory panel for ESPNW.

* * *

Friedman takes solace knowing that he does everything he can to cure people. Whether they survive or not, he is satisfied that he gives them quality of life even if it’s for a limited period.

When someone isn’t doing well or dies, he tries to store away his emotions and not discuss his patients. He has an insulation that absorbs the pain. It’s something he’s developed with time.

And yet his façade has chinks. There have been several times when he’s grown especially close to patients, and their deaths have “rocked him.”

No doctor can block out the emotion all the time, he says. “You feel the pain deeply, and you grieve as their family members grieve."

Ketring, his nurse clinician, has seen him at these lowest points. One instance that especially stands out to her is when he told two patients on the same day they must go on hospice. She previously had never seen him so upset and frustrated.

“He handled it with professionalism, grace, caring and compassion, but when the two of us walked back into the work room, it hit us hard. You can tell the emotion on his face.”

* * *

Tragedy entered Friedman’s life long before he became a doctor. When he was an 11-year-old growing up in Queens, New York, his father died from a sudden heart attack. Friedman responded by going into severe depression.

But his mom knew just the fix—Broadway musicals. Friedman saw “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Zero Mostel,” “Cabaret” and several other famous shows in what became a regular routine with his mom.

“It made me see there was beauty in life again,” Friedman says.

It also made him realize the value of staying positive.

By that time, Friedman already knew he would be a physician. Nobody else in his family had been a doctor. But as a nine-year-old in 1961, he became enthralled with “Dr. Kildare”— the drama TV series starring Richard Chamberlain about a young intern. Friedman eventually ordered a video set from China with copies of every episode, and began reading “Gray’s Anatomy” soon after.

It took him longer to become interested in neuro-oncology. He was set on pediatrics through his third year at Syracuse University's medical school and initially studied hematology. But while working in a hematology lab with Dr. Frank Oski—his mentor at the time—Friedman concluded that studying blood was boring. He wanted to study and treat cancer, and Oski suggested neuro-oncology.

In 1981, Friedman followed Kurtzberg to Duke where he began working in a lab with Dr. Darell Bigner—the current director of the Tisch brain tumor center. Friedman then led the development of Duke’s department of pediatric neuro-oncology before ultimately transitioning to adults to meet a growing demand.

* * *

Friedman is not tight-lipped. He’s outgoing and humorous. If you ask him a question, he can ramble on for 10 minutes in his light Long Island accent. But he is careful with his words and especially conscious about how he acts around patients.

He treats all of them as family. Handshakes are not enough for him—he wants hugs. And all of his patients call him Henry and love his hoodie and jeans, which he wears for comfort. He calls at least 20 of them every Saturday to see how they are doing.

When he has consultations and check-ups, he tries to be straightforward. You want to tell them what the problem is so they can begin receiving treatment as soon as possible, Ketring says.

But Friedman tries to stay positive around patients and families. He prides himself on his endless optimism and even helped coin the brain tumor center’s motto—“At Duke there is hope.”

Some people have criticized him, saying it’s false hope. In fact, five years ago an online feed was created titled “Dr. Friedman--Duke University--need to Vent!!” Although some of the comments praised his compassion and the Saturday phone calls, others said that he was too assertive.

Friedman acknowledges that he used to be more forceful. But that’s just because some patients and families did not listen to his advice and had a pessimistic outlook about survival chances. He says that if people don’t believe they can be cured, then they won’t bother to fight their illness.

“It’s like saying, ‘we’re going to go into the championship series and we can’t win.' And so you’ve lost already.”

* * *

On a Tuesday morning, Friedman is in a rush to finish his rotations. He has a conference call with the Food and Drug Administration in a few hours and cannot spend as much time with his patients as usual.

Still, he makes sure to catch up on their lives. He asks one who is a lawyer and in remission about his ongoing job search and sings the Mr. Machine jingle with another patient. “Here he comes, here he comes, greatest toy you’ve ever seen, and his name is, Mr. Machine!”

His final patient is a middle-aged man and Hollywood executive who has been doing well, but has a list of concerns.

The executive has struggled to remember things lately. Friedman tells him that memory loss is normal with a brain tumor. It might come back, but you should try using the "memory app, Lumosity. It works," Friedman says.

When the executive—whose name cannot be included because of patient confidentiality—discusses his shoulder pain and says it might be his rotator cuff, Friedman brings up his own shoulder and suggests physical therapy.

Once the check-up ends, the two men hug each other. Friedman tells him that he’ll be calling Saturday. The executive says it’s not necessary.

Friedman insists.